NEW BOOK

Journeys to the Bandstand by Chris Wong

Part 2: Excerpts from the Book

- EXCERPTS:

Charles Mingus

Natasha D’Agostino - PLAYLIST: Hear the Music

80 Songs That Shaped Vancouver Jazz on Spotify

68 Songs on TIDAL - WHAT THEY’RE SAYING ABOUT THE BOOK

- ABOUT CHRIS WONG

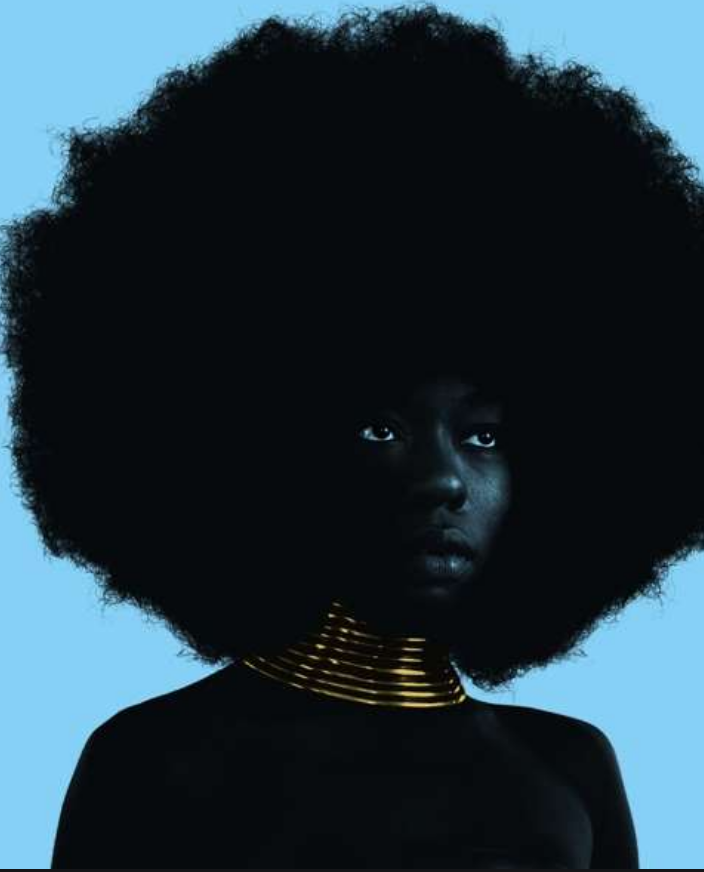

Natasha D’Agostino, performing at Frankie’s Jazz Club, September 24, 2017. (Vincent Lim photo)

JOURNEYS TO THE BANDSTAND:

THIRTY JAZZ LIVES IN VANCOUVER

Excerpts from the book

By Chris Wong

I went on a book tour. Kind of. It was a tour in the sense that there were multiple events to launch my book — Journeys to the Bandstand: Thirty Jazz Lives in Vancouver. Specifically, there were five events, and some of them involved two presentations on one day or evening. Geographically, however, it wasn’t really a tour because all of the events were in Vancouver and nearby Burnaby.

Regardless of how I label that two-and-a-half week period of book launching, it was intense and I learned a lot. What was my biggest insight? The parts of the events where I read excerpts from the book made the biggest impact on those in attendance. I could sense that from their focused expression and smiles/laughter at times.

There’s something about authors reading their own words, and taking the opportunity to add dramatic emphasis, which can make for a singular experience. Here in part 2 of the Kurated look at Journeys to the Bandstand, where I’m presenting excerpts from the book about jazz musicians, I can’t add those nuances. That’s okay, because the words speak for themselves about the artists I focused on, and about my book’s personal approach to exploring their captivating music and lives.

Enjoy the excerpts.

EXCERPT FROM CHAPTER 6

Mind of Mingus: Charles Mingus

Charles Mingus, performing at the original Cellar, January 1961. Photographer unknown. (Courtesy Dave Quarin)

THE CHAPTER ON CHARLES MINGUS looks at several weeks when the genius bassist/composer/bandleader performed in Vancouver at the original Cellar jazz club and in Victoria in January 1961. It was a musically rich and tempestuous fortnight. Part of the chapter also recounts a memorable encounter that a Vancouver jazz musician had with Mingus in New York, and that’s the focus of the following excerpt:

Rewind again, this time to 1976. That’s when Rick Kilburn had a close encounter with Mingus. The setting was Bradley’s, an intimate and beloved jazz club in Greenwich Village. Many great pianists performed there, and on this night, Jimmy Rowles was playing in his gorgeous style on an upright piano. Accompanying him on bass: Kilburn, a young, mild-mannered Canadian who grew up listening to and meeting jazz musicians. He enjoyed an idyllic jazz childhood and adolescence in large part because his dad Jim was one of the founders of the Vancouver haunt where fireworks went off when Mingus was on the bandstand: the Cellar. Jim was there the night Mingus allegedly grabbed a toilet plunger, and the guitarist heard the master bassist utter, “Anybody talks when I’m playing, I’m gonna plunge them out!”

At Bradley’s, Rowles and Kilburn were playing a bossa nova, when the bassist closed his eyes and started a solo. “From the table right next to me there was this gruff voice saying, ‘Don’t freeze, motherfucker.’” Kilburn opened his eyes to see none other than Charles Mingus. What did Kilburn do next? “I froze. I followed his instructions to a T [except for the “Don’t” part]. He stayed for the rest of the night and entertained the audience by giving me a lesson out loud all night long.”

During a set break, Kilburn asked Rowles to intervene. “I said, ‘He’s your friend. Tell him to shut up.’ Rowles said, ‘No, no, that’s Mingus. I’m not going to tell him anything.’ We made it through to the end of the night and by then I had built up my courage. I was going to go and just give Mingus hell. So I walked up to the table, he saw that I was mad, and he said, ‘Hey, I’m sorry. I shouldn’t have done that. I had no right to do it, but I’m high and, well, go get a piece of paper and a pencil and come back here, and I’m going to talk to you like an old man.’”

Kilburn got the supplies, and Mingus wrote notations that were directly relevant to playing jazz on the bass. “It had to do with phrasing,” said Kilburn. “They were devices to lock the time in, and it was invaluable. It took me about a year to get a grip on it.” Mingus claimed that the only other person he showed this information to was Scott LaFaro, the great bassist who died young in a car crash. Kilburn had met LaFaro at the Cellar when the bassist played there with Harold Land, so it meant a lot to receive this bespoke guidance from Mingus that apparently only one other musician had ever received.

The two bassists talked until Bradley’s closed, and then went to Mingus’ apartment nearby. Kilburn played Mingus’ basses and explained his connection to the Cellar. Mingus remembered the Cellar and the “machinations” that went with his unforgettable visit. They ended up hanging out all night. “He kept saying to me, ‘I know you, man. I love you.’ I guess he was trying to make up for shitting on me.”

After that night, when playing gigs, Kilburn would sometimes spot Mingus. “He’d be sort of sitting in a corner somewhere, like in the shadows, checking me out. I guess he was wondering if I was doing anything with the information he gave me. It turned out the next night [at Bradley’s] I came back to play with Rowles, and I started trying to do the stuff that Mingus had said, and Jimmy said over his shoulder, ‘Cut that shit out. Don’t listen to him. Go back to the way you were playing.’”

Classic. Mingus, when Kilburn encountered him, was both scoundrel and sweetheart. Heckling, dropping deep knowledge, and declaring his love.

Charles McPherson (alto saxophone), Lonnie Hillyer (trumpet), Charles Mingus (bass), and Dannie Richmond (drums), performing at the original Cellar, January 1961. Photographer unknown. (Courtesy Dave Quarin)

EXCERPT FROM CHAPTER 25

Endings Rarely Are: Natasha D’Agostino

Natasha D’Agostino, Capilano University graduation, June 5, 2017. (Chris Wong photo)

THE CHAPTER ON NATASHA D’AGOSTINO documents the singer’s artistic accomplishments and impact on Vancouver’s jazz scene before she tragically died in 2019 at the age of twenty-six. The first excerpt, from the beginning of the chapter, describes a gig that celebrated the release of her only album, Endings Rarely Are.

ONE SONG: Field of Green

It’s a night to remember for Natasha D’Agostino. On July 12, 2018, a few hours before she turns twenty-six, D’Agostino stands on the bandstand at a packed Frankie’s Jazz Club, brings the mic close to her, and starts singing with her distinctive alto voice. Right away her clarity of intent and whole-hearted passion radiate in the room. At the same time, she’s immediately in sync with the musicians in her quartet. In front of D’Agostino’s family and friends, along with jazz fans who knew it would be a special gig, the key elements of what make a compelling performance come together.

“We didn’t even take a second for it to jell,” said guitarist David Blake, who played that night with D’Agostino, bassist Paul Rushka, and drummer Bernie Arai. “There was no sort of stumbling to make it into something. It was something.” It was the CD release show for Endings Rarely Are, D’Agostino’s first album, which she recorded in August and September 2017 with these same musicians. Her performance represented something tangible and distinct. “A real significant, serious, artistic statement,” said Blake. “She just sounded so good.”

It went further than that. Blake recognized that he was witness to a young, gifted artist—his best friend—finding her voice. “I remember feeling when we played the CD release that it was even better than the album,” he said. “She was just growing so fast. It felt like every time I heard her, she was an order of magnitude better than the last time. So by the time we did the CD release, it just felt like now she really was figuring out what she was doing and how to do it.”

No one who was there had any reason to believe the evening’s joy was fleeting. Then less than six months later, D’Agostino was gone. In a cruel instant, a car accident ended the beautiful life she crafted as a musician, teacher, daughter, friend, explorer, and humanist. Words can’t adequately encapsulate the significance of her presence and the enormity of her loss to loved ones and Vancouver’s jazz community. “For so many of us, her death is the deepest grief and a seemingly pointless tragedy,” said D’Agostino’s friend Tracy Neff. “It is definitely the one event in my life so far that has made me truly question the meaning of all of this. Like, if she’s not here, why are we all here? Why her?”

They’re profound questions that elude definitive answers. But as the months went by, it became increasingly imperative for me to explore and document D’Agostino’s life to ensure her story endures. No one appointed me her biographer. I took it upon myself to chart D’Agostino’s course because she embodied the ideal of achieving meaningful artistic expression, not just by drawing from her striking talent, but through determination, curiosity, and fearlessness.

THE SECOND EXCERPT recounts the first time David Blake and D’Agostino performed a gig together, and the surprising way it unfolded.

In 2015, David Blake met D’Agostino when both were part of a NiteCap performance. Right after that, D’Agostino contacted him about playing a duo gig together. When they showed up at the gig, Blake asked D’Agostino what she wanted to play. Her noncommittal reply: “I don’t know, what do you want to play?” Blake thought her response was bizarre because he was used to working with singers who were experienced bandleaders, with their music fully organized well ahead of time.

“At first, I was like, ‘Oh fuck, this is going to be tedious.’” He asked the question again, and she replied the same way. Then Blake suggested a standard, which D’Agostino said they could try, but she admitted never having sung it before. “Again, I was just like, ‘Oh my God, what is she doing?’” The awkward dance continued, with Blake saying they should do something she knows, and D’Agostino insisting that they do the tune he suggested. Which they did. “I think I played a little intro and she started singing, and it was like she had been singing this song for forty years. Like she knew every detail and every little thing. She just sang it like it was her song. And I was in awe the whole time.”

The rest of the gig proceeded in the same two-step dance, with Blake proposing a song and D’Agostino saying, “Yeah, I’ll try this one,” and tune after tune “knocking it out over and over again.” For Blake, his emotions during the gig had run the gamut, from curiosity to exasperation, and then incredulity and finally, wonder.

Quotes about Journeys to the Bandstand

“The first thing you notice holding a copy of Journeys to the Bandstand: Thirty Jazz Lives in Vancouver by author Chris Wong is the sheer heft of the text. Clocking in at over 600 pages, the book is proof that B.C.’s improvised music scene has a long and lively history. It’s testament to Wong’s skill that the book blazes by like a be-bop sax solo …

Wong opens up the world of Vancouver jazz by bringing long lost names to life right up to events such as the Jazz at the ‘Bolt festival in 2023. Chapters focus on individuals while explaining their relevance to the greater scene.

This means Journeys to the Bandstand avoids the curse of many music histories where the minutiae of dates, individuals and incidents are so complexly intertwined that the reader requires a flow chart to keep up. Instead, we are treated to stories such as the role that Vancouver played in the development of no less a titan of the genre than Ornette Coleman …”

—Stuart Derdeyn, Vancouver Sun and Province

“I have never read a book so fast in my life! Chris did an exceptional job. It’s an absolutely wonderful book and it was so incredible to learn more about the history of jazz in our city and to read about the lives of people that I thought I knew really well. I can’t really put into words how fantastic it is … Congrats Chris Wong. You’ve contributed an incredible thing to the legacy of this city and to the legacy of this music.”

—Cory Weeds, saxophonist, founder, Cellar Music Group

“I can’t say enough good things about this book. It’s fantastic. Chris Wong is such a good writer. I started out thinking I would read just a few of the chapters [on] musicians I was particularly interested in. But I wound up reading all the chapters in order. They’re so good. I can’t recommend it highly enough!”

—Brian Nation, founder, Vancouver Jazz Society & vancouverjazz.com

Read more quotes on Chris Wong’s website.

Hearing the music: the playlist

Listening to recordings was critical to my understanding of each person that I focused on in Journeys to the Bandstand. At the back of the book, there’s a Selected Discography that lists recordings I wrote about in the book. I’ve read books about jazz that are long on biographical detail about artists but short on actual descriptions and reactions to the music they made. So it was important to me for this book to include passages about the featured artists’ extraordinary music.

Beyond the book’s 605 pages, I went a step further in shining a light on the artists’ music. I compiled an 80-song Journeys to the Bandstand playlist in Spotify. Each song on the playlist is relevant to the book in different ways. It includes a range of music in different jazz styles—from straight-ahead to avant-garde—by instrumentalists and vocalists.

Example: the version of “How Deep is the Ocean”, by alto saxophonist Charles McPherson (interviewed for several chapters in the book, including one on Mingus) and a local rhythm section, was recorded live at Cory Weeds’ Cellar Jazz Club. It includes a four-minute and twenty-two second solo by Vancouver’s Ross Taggart on piano that has entranced me for years, and which I described in detail at the beginning of the chapter on Taggart.

Enjoy the music in the Spotify playlist.

I also created a 68-song version of the playlist in TIDAL. This is specifically for people who prefer to use TIDAL. It’s shorter because not all of the songs in the Spotify version are available in TIDAL.

Enjoy the music in the TIDAL playlist.

To learn more about Chris’ book and how to buy it, see his website.

This is the second in a two-part series of Kurated posts about Journeys to the Bandstand.